A

Maximal tori: Overview

Maximal tori: overview

We now want to understand groups more general than and . One of the key ingredients we used to study those special groups was the weight diagram, which encoded the information about how a representation decomposes under the action of a the diagonal subgroup: inside and inside .

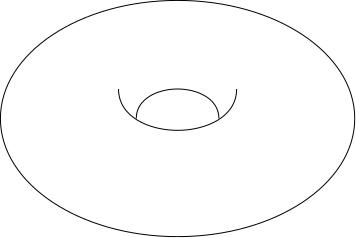

It's called a torus by analogy: is topologically a 2-dimensional torus (doughnut shape) as a torus has two angular coordinates like . Higher dimensional tori are defined to be products of more copies of .

A torus is called

We're focusing on maximal tori because these will give us the most refined decomposition into weight spaces: if you pick a submaximal torus you will always be able to decompose your weight spaces further using the action of the additional -factors of a bigger, maximal torus. For example, if we'd just used in , we wouldn't have seen the nice 2-dimensional weight diagrams that gave us so much information: we would only have seen projections of these diagrams down to a 1-dimensional line.

Examples of maximal tori

For , the diagonal subgroup is a maximal torus. This specialises to our earlier examples for and .

The subgroup of rotations around the -axis is a maximal torus in .

In , we can find the 2-dimensional maximal torus:

In we can still only find a 2-dimensional maximal torus: There's no room for another diagonal 2-by-2 block.

This is one of the first points where we see a significant difference between odd-dimensional rotation groups and even-dimensional rotation groups: relative to the dimension of the group, there's a lot more off-diagonal stuff in odd-dimensional rotation groups.

Theorem

Let be a compact, path-connected matrix group (bounded matrix entries). Then:

-

contains a nontrivial torus if is nontrivial.

-

Any element of is contained in a torus.

-

Any torus is contained in a maximal torus.

-

Any two maximal torus and are conjugate, i.e. there exists an element of such that .

We will not prove (4): the proof would take us too far away from the main themes of the course. The proof uses some very cool ideas from topology, including the Lefschetz fixed point theorem. You can do an in-depth project on this, but it does require a bit of background in topology. We will also not prove (2) fully, though we will make a remark about what we would need for this.

Before we move on to the proof, here are some examples to see why the hypotheses of the theorem are necessary.

Suppose is the real numbers with addition. Since the real line doesn't contain a topologically embedded circle, there's no way to get a nontrivial torus in . The real line is path-connected, but not compact, so we see that compactness is necessary.

The assumption of path-connectedness is necessary for part (2) of the theorem. For example, consider , the group of orthogonal 2-by-2 matrices. This has two components: the rotations and the reflections. Each component is topologically a circle. The identity component (the subgroup of rotations) is a torus; this the only torus (since any torus is connected and contains the identity) and none of the reflections is contained in it, so the claim that every element of is contained in a torus fails.

Pre-class exercise

Can you see why the tori we have been using in and are maximal?